General Science is part of Pao School's core curriculum and, at the Middle School, it focuses on four main areas: Biology, Chemistry, Physics and Scientific Enquiry. Scientific Enquiry cultivates myriad different key skills in students, such as the ability to judge scientific evidence and plan scientific investigations, as well as record and analyze data. As students develop these skills, they become more active science learners, while consolidating their knowledge of biology, chemistry and physics.

Both Chinese and international teachers deliver the Middle School's science courses, which helps to cultivate students' bilingual learning ability and ensure that students know core vocabulary in both languages. The course content for both Chinese and English language science is complementary, allowing the teachers to meet corresponding curriculum standards each semester. And, as a core driver in promoting strong science learning, Pao School strives to introduce subject teachers with superb academic qualifications.

One such teacher is Ms. Weng Meiqian, who has been with Pao School since 2015. Before joining Pao School, she worked at Shanghai Xinhua Hospital after obtaining her PhD in Pediatrics from Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine. Ms. Weng also spent time working in the US as a lecturer at Harvard University Medical School, allowing her to gain rich scientific teaching experience. As an expert who has experienced education in both China and the United States, she feels that the pedagogies in the two countries are quite different, particularly in science teaching.

With that in mind, Ms. Weng decided that once she returned to China, rather than working in a scientific research institute, she wanted to become a middle school science teacher. She felt she could make the greatest contribution to Chinese science education at the middle school level. In a trip back to Shanghai a few years prior to her returning to China, she had a chance to visit Pao School and was deeply impressed with the school's combination of Chinese and Western culture, its strong academics, the core values of compassion, integrity and balance, and the founders' educational philosophy.

Following the school’s aim for continual improvement, the Middle School's leadership team and science department are enthusiastically supporting Ms. Weng's initiative. The teachers hope that in middle school, which serves as the bridge between the primary and high school, they can cultivate students' basic scientific literacy and train them to think like scientists.

"It is important for students to master knowledge and skills in accordance with the requirements of the syllabus, but I also hope to cultivate their critical thinking ability. I ask them, 'What do you think? Can you find evidence to support your ideas?'" Ms. Weng explained.

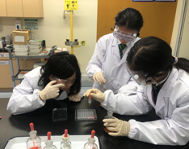

Science Class

Ms. Weng carefully designs her classroom teaching content – such as the "human anatomy" biology unit that focuses on the structure and function of the body's organs – to further develop her students’ thinking abilities. For Ms. Weng, it is important that students be active learners and explore the subject matter independently.

This ethos is reflected in her teaching methods. For example, she asks students questions such as: What is the main organ responsible for digestion and nutrient absorption? The stomach or the intestines? For this question, Ms. Weng prepared materials that students first reviewed, and then encouraged them to discuss the topic amongst themselves. This process aided them to better master the course material, with Ms. Weng explaining, "The student-led learning process helps train them how to think."

Ms. Weng also carefully designs homework for students that helps further hone their thinking. For instance, after teaching Year 7 students about haematology and sickle-cell anaemia, a genetic disease that causes a deficiency of red blood cells, they were then asked to write an essay. The essay, entitled "Genetic Mutations in Sickle-Cell Anemia-The Power of Natural Selection," helped students to understand the link between sickle-cell anaemia and malaria, while also enabling them to explore the significance of genetic mutations. Because Ms. Weng also prepares ample materials for students to read to help them prepare to write the essay, this exercise also burnishes their non-fiction reading skills.

Ms. Weng notes that tackling such scientific coursework is challenging for students of this age, as some of the concepts stretch the boundaries of their knowledge. Still, many students can thrive if they work hard. Ms. Weng is impressed with the first drafts students submitted for their essays, from the logical rigour of the writing to the completeness of their thesis statements.

At the end of the process, she chose some outstanding essays to review in class, pointing out their strong points, such as how to find scientific evidence and use it to support one's argument. After such discussions and revisions, the students not only understand the importance of data but also learn how to write effective scientific arguments and formal papers.

Leo (7F) says that the toughest part of the essay writing process is sifting through the vast troves of information and selecting what is most relevant. This is especially difficult as some of the writing assignments deal with things removed from his everyday life experience.

"I first put together a basic outline based on what I learned from my previous reading and include parentheses where additional information is needed to strengthen the essay's arguments," Leo says, explaining how he approaches the essay writing process. "After the outline is complete, I then look for data that can support the main ideas expressed in each paragraph. I find that this allows readers to follow my ideas and better understand the main points of the overall paper."

Michelle (7A) says that her biggest gain from the writing process is learning how to think independently, then gather material to support her arguments and organize the material cohesively. When writing about the link between sickle cell anaemia and malaria, she drew a mind map with the former disease on one side and the latter on the other. Then, she filled in the information connecting the two illnesses on the respective branches of the mind map. "This allows me to see the connection between two seemingly unrelated diseases," She says.

It is also natural that parents closely follow their children's schoolwork. During this process, Yuki’s mother (7A) was deeply impressed by her daughter’s homework and wrote an email to Ms. Weng noting her observations:

"Yuki has been reading a lot of scientific literature, and when I asked her some questions about her essay, her responses were very thorough. The homework has helped improve her ability to think and study independently. At the same time, thanks to the teacher's detailed feedback on her assignments, Yuki understands how she should revise her writing in the future. She also uses software that can detect plagiarism and is thus inclined to use her own insights whenever she can and not rely too heavily on citations. I am surprised to see she has this level of self-awareness, but as a parent, I am very happy to see her understanding of this subject blossom, and I believe her ability in science will also benefit her performance in other subject areas."

For Ms. Tina Tao of the Science Department, homework is also a crucial part of the learning process. An experienced teacher, Ms. Tao was attracted to Pao School by its bilingual environment and advanced educational concepts. Since joining the school in 2013, she has been exploring how to combine new curriculum standards to cultivate students' intellectual curiosity and innovative thinking. She believes that homework assignments must go further than merely focusing on the examination of scientific knowledge and rote memorization. She feels that these approaches will not whet students' appetite to learn about science and will hinder the development of their scientific thinking ability. To combat this, she designs more unique types of homework that provide an outlet for students' creativity.

For example, in the unit Water and Humanity, which focused on the water cycle and water pollution, students were able to choose their own approach to their homework. As they were free to approach the assignment creatively, the students produced some outstanding and unique work:

Students built models and shot videos using waste materials, boosting their

scientific vocabulary and presentation skills (Video by Y6E Smile)

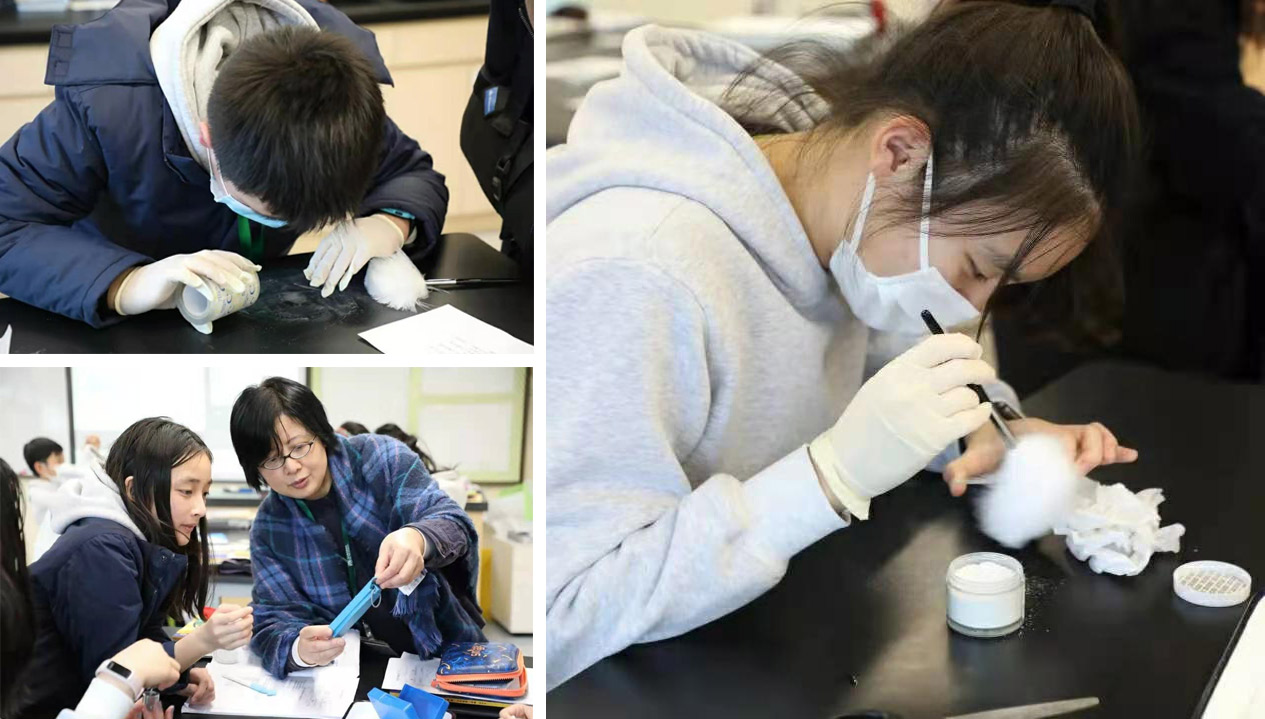

Ms. Weng and Ms. Tao also set up a co-curricular club that focuses on forensic science, which also reviews the students’ previously learned classroom content and homework. The two teachers chose this theme to stimulate students' interest in science outside the classroom and step away from purely academic classroom-style teaching methods. In doing this, the students are encouraged to build good long-term study habits and discover their own interests. After all, Ms. Weng says, this is a key goal of education at the middle school stage.

Reflecting the students’ study of blood analysis in the classroom, the forensic science CCA teaches students how the information contained in the blood can provide crucial insights that help investigators solve cases.

"The forensic science club has many different activities, including fingerprint extraction and identification, textile identification, as well as writing and discussion of forensic science essays," Ms. Tao says, adding that the club received an enthusiastic reception from students soon as it was launched. Soon after it started, the two time periods quickly filled up.

Textile identification

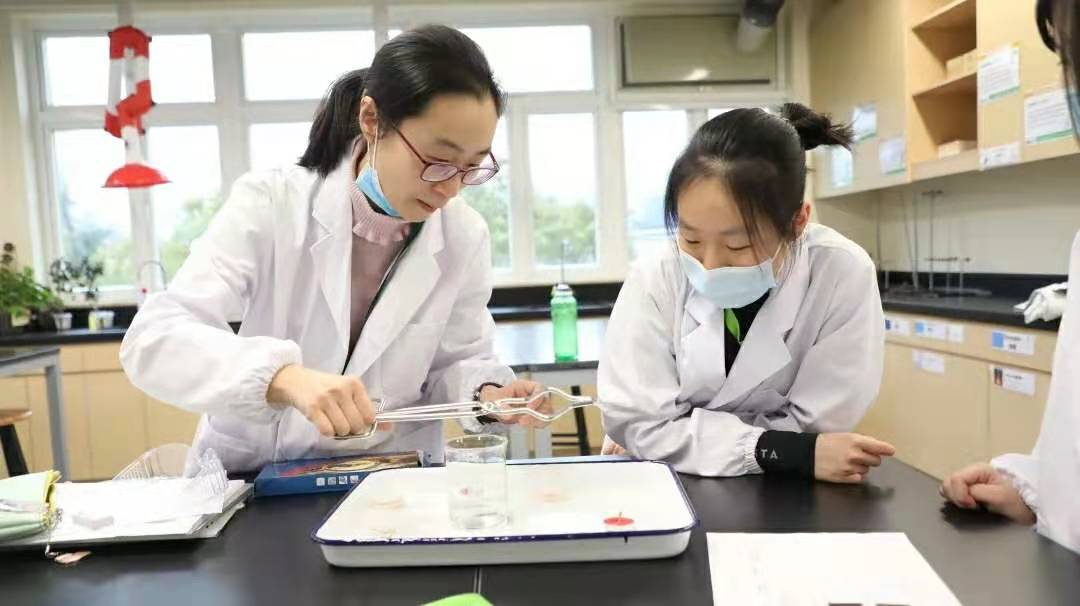

In the forensic science club, Ms. Tao has presented various cases to students that allowed them to understand the importance of identifying blood type in forensic science casework. In one exercise, the students first were given four numbered unknown "blood samples," and then used two chemical reagents called serum A and serum B. The students added the reagents to their four blood samples to see if any chemical reactions would occur and reveal information about the contents of the blood. Based on their observations and the principles of blood coagulation they learned prior to the experiment, the students were tasked with identifying the blood type of the four samples.

Alongside taking a hands-on approach, Ms. Tao also prioritizes the safety of the students. For example, she has improved the traditional blood sampling experiment by simulating the blood coagulation reaction with a variety of chemical reagents. And for the experiment to be more realistic, red ink was added to simulate the colour of blood.

←

Bloodstains

The students measure the influence of height on bloodstains shape.

Blood type

→

The students use chemical reagents to identify blood type.

"The club's activities allow students to both learn about some of the basics underlying forensic science and improve their own exploration ability and dialectical thinking. The activities also include a writing component, which incorporates what they learn in their humanities courses. Finally, after the activities are over, students follow up on what they learned by reading detective stories."

——Ms. Tao

The pandemic has shown us all the uncertainty of today's world. No one knows exactly what the future will bring, perhaps the knowledge we learn today may not be considered correct in the future. Therefore, our students need to be independent and to think for themselves in a scientific manner. A teacher's job is to cultivate that crucial ability in students, demonstrating to them how to approach scientific problems in a comprehensive way, from thinking to evidence collection to building strong arguments.

——Ms. Weng

Join our upcoming info session for Middle School transfer students to learn more about our curriculum pathway, co-curricular activities, campus life, etc.

Who should come: Parents of students currently in Y6 or Y7

Time & Location: Tuesday, March 30th, 2021 (Details will be sent via email)

Registration: Please scan the QR code below to submit the registration form.