Professor Kim Plunkett, Director of the Oxford University BabyLab at Oxford University in the United Kingdom, visited Pao School on 25 October to speak about the mechanisms of change that drive linguistic and cognitive development in infants and young children. The lecture was one of a series of educated-related events being held to mark Pao School’s tenth anniversary. More than 100 parents and numerous Oxford alumni attended.

Dr Plunkett’s work focusses primarily on word recognition, word learning, semantic development, and category formation during the first two years of life.

In 1992, Dr Plunkett established the Oxford BabyLab, a research facility for the experimental investigation of linguistic and cognitive development in babies and young children.

Ties between Oxford University China are steadily growing, noted Pao School co-founder Philip Sohmen, as he introduced Dr Plunkett to the audience. Mr Sohmen is an Oxford graduate and active in the Asia-Pacific Oxford alumni network. There are now 1,000 Chinese students at Oxford, making them the second-largest group of overseas students at Oxford after those from the U.S. There are also 4,700 Oxford alumni in China. Furthermore, there are a growing number of collaborations between Oxford University and institutions in China, some which date back several decades.

A fundamental problem in studying infants’ development is they are unable to tell us what they know. The youngest ones are unable to speak while the older ones may not understand what someone is asking them.

Dr Plunkett says,

‘We have to devise cunning methods to figure out what they know and how they’ve learnt what they know.'

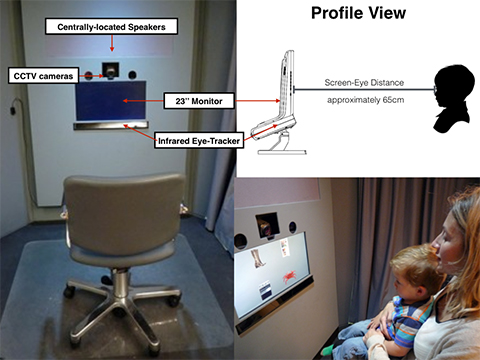

Eye tracking

The method works as follows: We hold two cards up in front of the baby, such as a bird and a frog, and say ‘bird’. If the baby consistently looks at the image of the bird, we can infer the infant understands what’s being said, even if the child cannot itself say ‘bird’. With recent advances in technology, infrared light can be sued to electronically track an infant's eye movements, makes possible more subtle experiments.

Neuroimaging

Neuroimaging is used in a similar manner to eye tracking. A baby is presented a baby with an image of a bird and a frog, and we say ‘bird’, and it is possible to see which parts of the brain are activated by that, and whether ‘any part of the brain is activated when we say a nonsense word or a word not on either of the cards’.

‘Even in infancy we seem biologically programmed to intuitively make sense of the world, to assign names to things,’ Dr Plunkett says.

The Oxford BabyLab has also researched the impact of sleep on a baby’s language acquisition. The experiments involved dividing babies into two groups, both of which were taught new words at the same time. One group of babies went to sleep after being taught the new words, while the other group did not. The researchers found that the babies who had the nap were able to remember more words than those who had not.

‘We can see already at three months of age the impact of sleep on the impact of children’s memory development. Sleep is not a passive process. It’s good for adults; it’s good for infants,' Dr Plunkett said.